Utopian Enemies of the Better

Lesser evils should be preferred over greater ones

One of the most common fallacies in applied ethics and public policy is to reason from “X is good” to “Doing Y without X should be prohibited”. Presumably the implicit thought is that by prohibiting not-X, you’ll get more X. But the prohibitors fail to appreciate that they haven’t actually prohibited not-X (they haven’t magically legislated an abundance of X directly into existence); they’ve just prohibited a certain way of doing Y (without X), which still leaves the worse option of neither X nor Y on the table.

For concrete examples, consider:

Banning “sweatshops” (i.e. boycotting the needy) without providing better employment options, leaving many with only worse options like subsistence farming. That is, they’re left with neither a good job nor even the “lesser evil” of a “sweatshop” job.

Refusing the global poor “guest worker” access to first-world labor markets (because it would be “unjust” to treat them as “second-class (non-)citizens”, working here without eligibility for welfare benefits or a pathway to citizenship), leaving them without either first-world welfare benefits or a first-world job.

Banning cheaper forms of construction in places where housing demand far outpaces supply, because “windows should be a human right.” Anyone who wanted the opportunity to live in a cheap (windowless) apartment in Austin may be left with alternatives that they value as overall worse. (Perhaps they now can’t afford any housing in Austin. Or they pay more for a windowed room at the cost of no longer being able to afford other goods or opportunities that they valued more highly.)

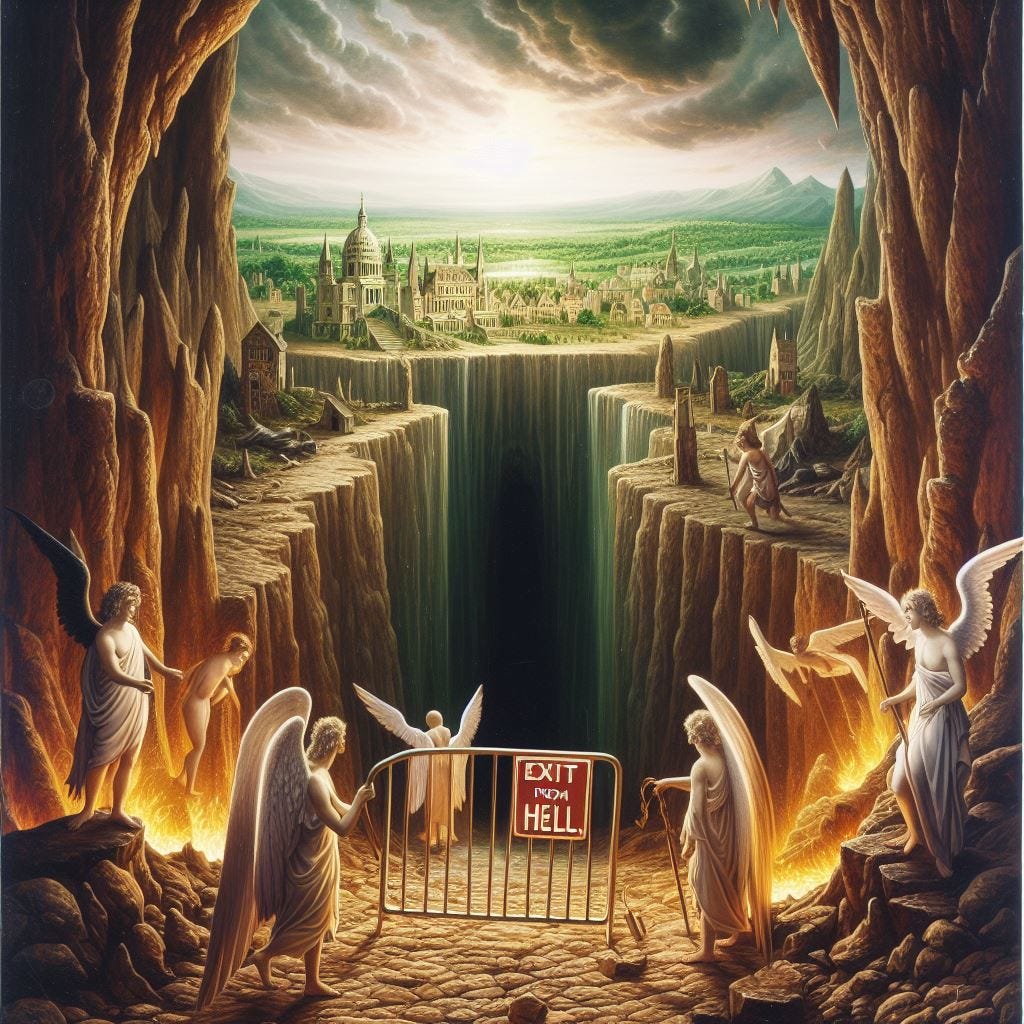

Removing options for supposed inadequacy, whilst failing to guarantee better alternatives, strikes me as a disturbingly common moral pathology. It sounds good to protest against lesser evils, and to uphold a greater good as more ideal. And, indeed, the greater good presumably is more ideal (all else equal). But if you don’t have a plan in place to actually provide an abundance of greater goods, simply banning lesser evils risks leaving us with only the greater evil.

So, as a general (defeasible) rule, I think we should be very wary about removing options—especially for those with few options to begin with. I worry that many on the political Left, especially, do not sufficient appreciate the potential costs here. If we want more good things, we should want policies that promote more good things—i.e., abundance. Banning lesser evils is rarely an effective means to creating more good.

Now, one can always argue that well-being will be best advanced by preventing certain exploitative exchanges. Perhaps banning “Y without X” will lead to more of “Y with X” rather than to “neither Y nor X”. It’s possible! But that’ll typically be a complex empirical issue, not settled by simple-minded slogans about how X is so good that it ought to be a human right. Anyone who actually cares about those affected by their policy advocacy must at least be concerned about the possibility that the greater evil of “neither Y nor X” (or, at least, “less of both Y and X”) would instead result. It would be a kind of callous utopianism to not care about this prospect at all.

Just as we shouldn’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good, so we shouldn’t let the good be the enemy of the better. Some conditions might fall below our standards for seeming outright “good”, but as long as they’re less bad than the actual alternative (often: the unchanged status quo), we should welcome the change nonetheless.

Richard, I like your articles, but I'd like to see more back and forth with your opponents.

Have you considered trying to do a podcast with a deontological partner? Perhaps semi-regularly? I know you had a video with Michael Huemer once, but I'd like to see more of that and with more philosophers. Discussion would be more useful than outright debate.

Just to throw out one name, I think Eyal Zamir is good deontological theorist, but surely there are many.

I'm not sure how best to woo philosophers onto a podcast, but Robinson's Podcast seems to have been remarkably successful at this. Admittedly, he mostly just lets them talk and doesn't push back much.