Analytic vs Conventional Bioethics

Intellectuals should do more than launder vibes

I’m looking forward to visiting NYU later this week to talk about genetic reproductive freedom at the 5th Annual Philosophical Bioethics Workshop!

My talk was partly inspired by a survey that seemed to confirm all the worst stereotypes about the field of bioethics as uncritically laundering conventional moral platitudes (of a broadly progressive-egalitarian stripe). So I’m especially curious to hear more about how the philosophers in the field, who often do good and important work, feel about the larger field—since so much of the latter strikes me as worse than worthless.

In general, I think there’s an important distinction between those who approach practical ethics in a broadly “analytical”, critically philosophical way, versus those who uncritically regurgitate whatever conventional attitudes (often highly politicized) they’ve previously imbibed. This division seems especially stark, and especially high-stakes, when it comes to bioethics.

To illustrate, this post will briefly highlight some especially revealing results from the survey, before shifting to the topic of my talk.

The Bioethics Survey

Pierson et al. (2024) surveyed 824 U.S bioethicists, with results summarized here.

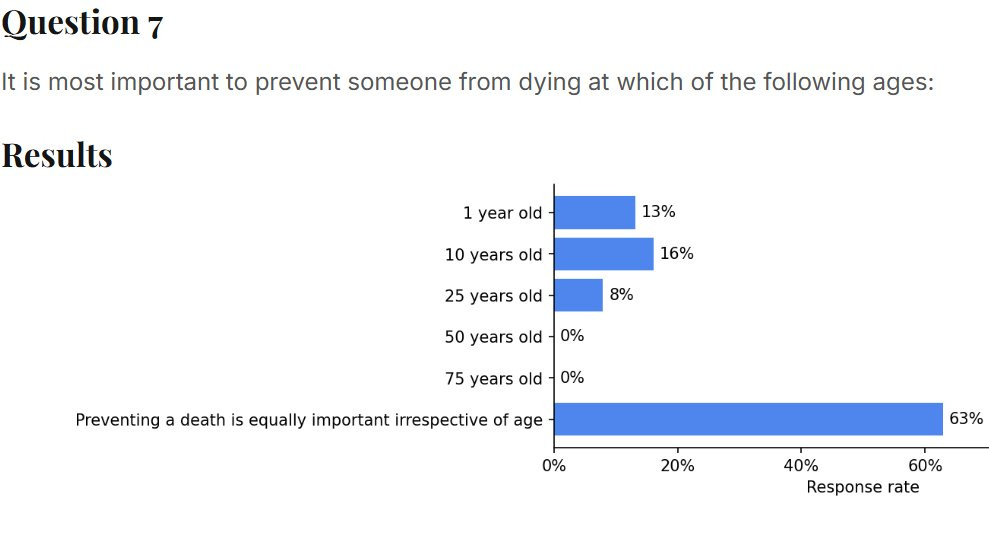

Some of the results were shocking. For example: a significant majority of bioethicists apparently believe that every life-extension is equally important irrespective of its duration. (Or, more plausibly, have not adequately reflected on the conceptual truth that what we call “preventing a death” is really just extending life by a variable period.)

It’s a real worry for a field when an outright majority of its practitioners are this blatantly incompetent, especially if they exert any influence over high-stakes medical allocation policies.1

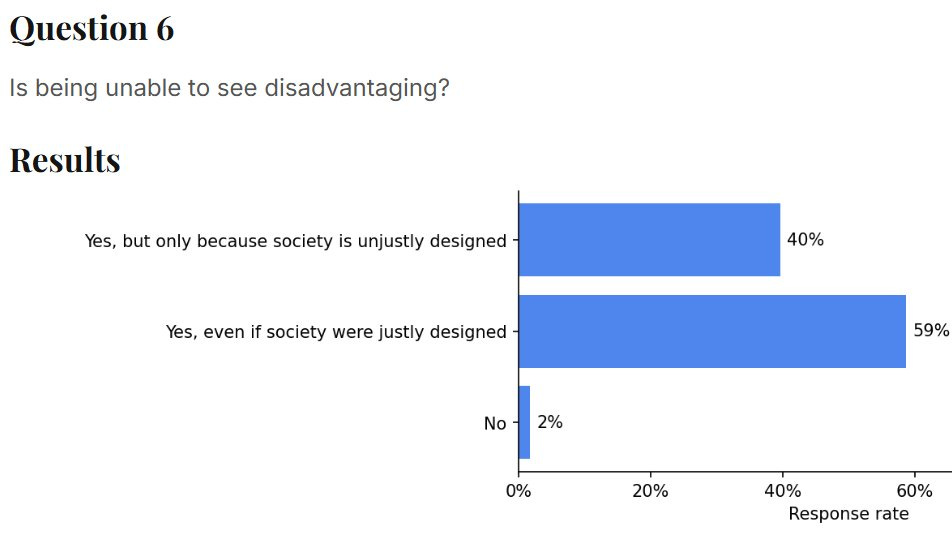

It’s also embarrassing that 42% are this unhinged from reality:2

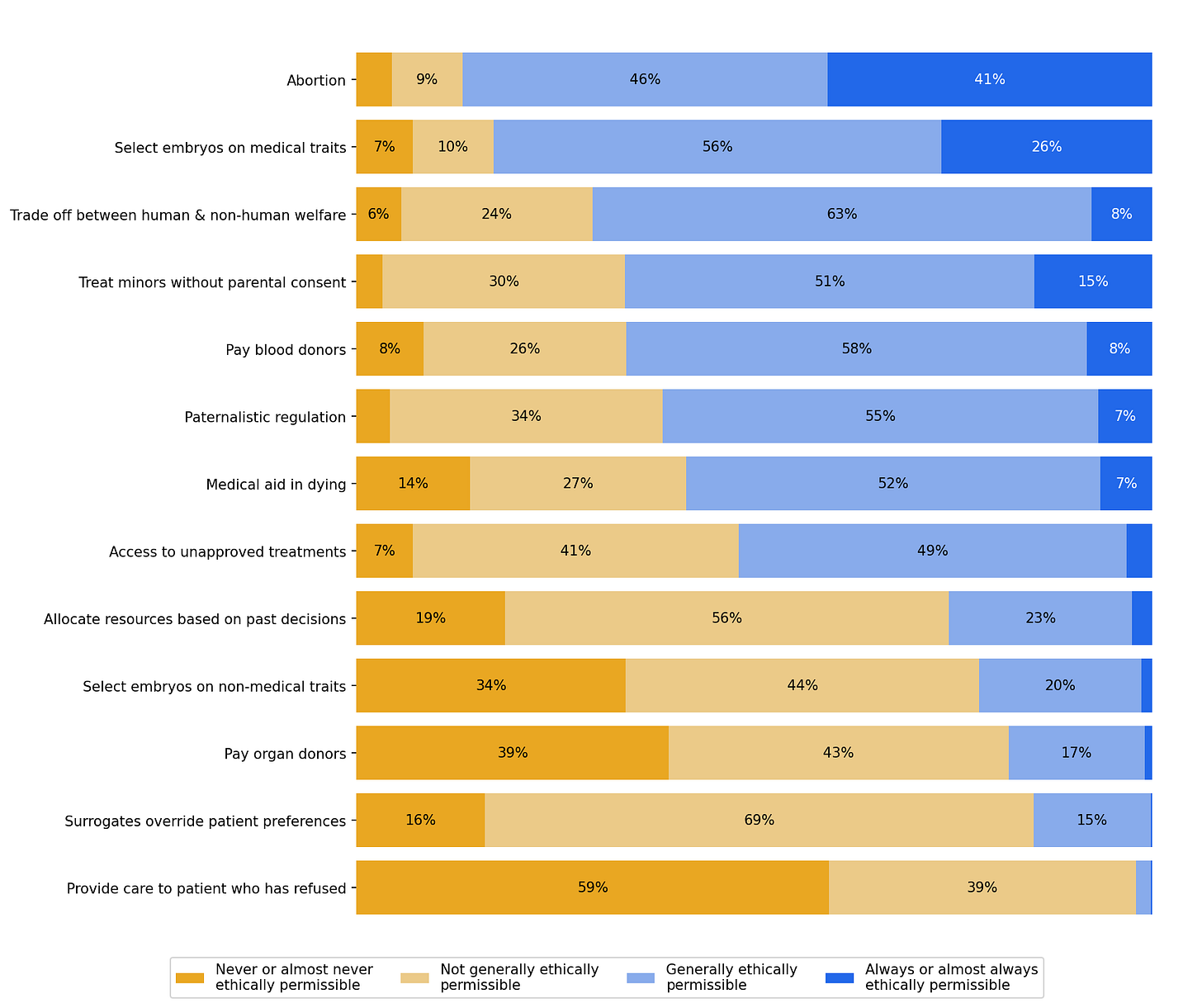

Then there are the main results, showing (among other things) deplorable opposition to life-saving policies to encourage organ donation. And—the inspiration for my talk—less support for selecting healthy embryos than for terminating them!

Confusing Freedom and Fascism

As a rather stark example of bioethicists blindly following vibes, consider the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on “eugenics”. Previous academic supporters of reprogenetic technology made the terrible branding mistake of calling their view “liberal eugenics”, which conveys all the wrong connotations and is basically guaranteed to cause a total cognitive shutdown in any low decoupler engaging with the topic.3

Since anything with a bad word in its name must be bad, the SEP article goes so far as to claim that it is “difficult to see the differences” between empowering would-be parents versus forcibly sterilizing them against their will. I’m not kidding! They write: “Insofar as the liberal [reprogenetic] project is not [solely] interested in the welfare of particular people but in producing… the best world possible, it is difficult to see the differences with the old eugenics.” Apparently anyone who aims at a better future is, in light of the non-identity problem, indistinguishable from Nazis.

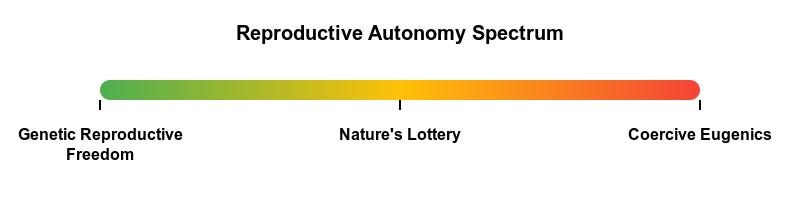

To better enlighten these benighted souls, I even made a diagram:

You see, to know whether a project is good or bad, it isn’t enough to know that its proponents intend a better future. You need to know something about what, concretely, they propose to do. If they will use coercive authoritarian means, exerting power over others in flagrant violation of bodily autonomy, then that’s objectionable. Not because they meant well, but because they violated basic human rights. By contrast, if someone else’s well-meant plan involves empowering individuals to have more control over their own lives and reproductive choices, then—so long as you’re not a complete fucking moron—you may be able to spot a morally relevant difference or two.

Status quo bias is no excuse for illiberalism

I’m always blown away by how deeply infused conventional attitudes are with status quo bias, especially in bioethics.

Considering our current topic, for example, people constantly worry about (i) parents making bad choices, and (ii) unequal access to reprogenetic technology resulting in unjust inequalities. By contrast, you’ll almost never hear anyone else so much as notice the—plausibly far greater—status quo risks of (i) preventing parents from making good choices, and (ii) cementing existing unjust inequalities of genetic privilege.

For example, it is deeply unfair that some kids are genetically predisposed towards severe depression or other potentially fatal illnesses, through no fault of their own. This is a deep injustice that reprogenetic technology could help to remedy. Yet somehow, the risk that biomedical conservatism may unjustly prevent loving parents from undertaking life-saving interventions on behalf of their future children is not a concern that even receives a mention in the SEP article mentioned above. They’re totally blind to their bias.

To help make it more vivid: suppose that humanity had always exercised genetic reproductive autonomy during pregnancy. Imagine, for example, that meditation-guided nature magic allowed pregnant women to mentally modify their embryo’s DNA to their liking: pre-empting health problems, and enhancing the capabilities of her future child, in line with her personal values and priorities.

What would you think of bioethicists coming along and demanding that you stop improving your future child’s prospects via this means? What if they passed a law to force you to stop, leaving you (and your future child) at the mercy of nature’s lottery? I don’t know about you, but I would be furious. And I think we should be similarly outraged by the real-world agents of reprogenetic illiberalism, who are trying—without adequate justification—to coercively prevent parents from acquiring this (technologically aided) magical power.

Conclusion

Bioethics is incredibly important, which means it can be extremely harmful when done poorly. To be done well, it needs to draw upon rigorous philosophical analysis and conceptual understanding. Bioethicists need to seriously reflect on the nature of death, and what it means to “save” a life, in order to coherently evaluate and prioritize between competing life-saving life-extending interventions. And to understand the moral significance of reprogenetic technology, we need to go beyond vibes and lazy associations (especially on the basis of misleadingly provocative labels), and instead seriously think about how the promise and peril of the technology compares to the very real and significant costs of the status quo.

In an interesting podcast episode, Pierson, Largent, and Persad discuss the survey, and related criticism of bioethicists, in a very general way. For example, they diplomatically talk about the “credentialing problem” for bioethicists. I’m less optimistic that “credentials” would automatically bestow intellectual competence on the 63% here, but maybe if they were taught sufficiently differently…?

Or perhaps just willing to assert obvious falsehoods in order to signal their political sympathies? Still unprofessional behavior for anyone in a putatively truth-seeking discipline, IMO.

Next up: public health officials celebrate the “smallpox genocide” of the mid-20th century, which ethnically cleansed the virus from its indigenous lands, leaving only a bare few survivors enslaved in maximum security biolabs.

I don't agree with everything you say here. Specifically, I think a sufficiently just and accessible society could disadvantage people far far less than it does now, to the point where it might only be as bad as being genetically short or having skinny arms. And I do worry about gene selection being only available to rich people, if it's sufficiently expensive.

That said, I don't want to come off as a critic. This is a good and thoughtful post, I agree with lots of other parts of it, and I expect I'll be linking it pretty often in future debates. I've long been bothered by vibes-based morality, and you've given a pretty sound case against that. I did want to ask what your take was on some discourse I've seen around the idea of genetically selecting away autism.

The idea that there's no such thing as "saving," only prolonging a life, and that interventions that prolong life by more are more valuable than those that prolong a life by less, makes a lot of sense to me.

That said, like children, there are also other categories of people who, statistically, are likely to live longer than others. E.g. women, white people, rich people, etc. This principle would imply that, ceteris paribus, saving the life of a woman is more valuable than saving the life of a man, of a white person more than of a black person, a rich person more than a poor person, a European more than an American, etc. And those would seem to be on some pretty shaky ethical ground. I'm not really sure how to reconcile these ideas.