From Autonomy to Utility

Deontology as Defection; or The Case for Waiving Non-Utilitarian Rights

[An excerpt from Beyond Right and Wrong.]

Some rights can be expected to promote overall well-being. Utilitarianism endorses these. Other rights lack this utilitarian property: they protect people against harmful interventions, but at greater cost to others who miss out on helpful interventions as a result. Utilitarians reject these putative rights. Considerations of ex ante pre-commitment support their stance. Whatever rights we suppose individuals to start with, we’ll see that they’re rationally required to waive all non-utilitarian rights on condition that others do likewise. So, respect for individual autonomy should swiftly lead us to (something in the vicinity of) utilitarianism, even from a starkly non-utilitarian starting point.

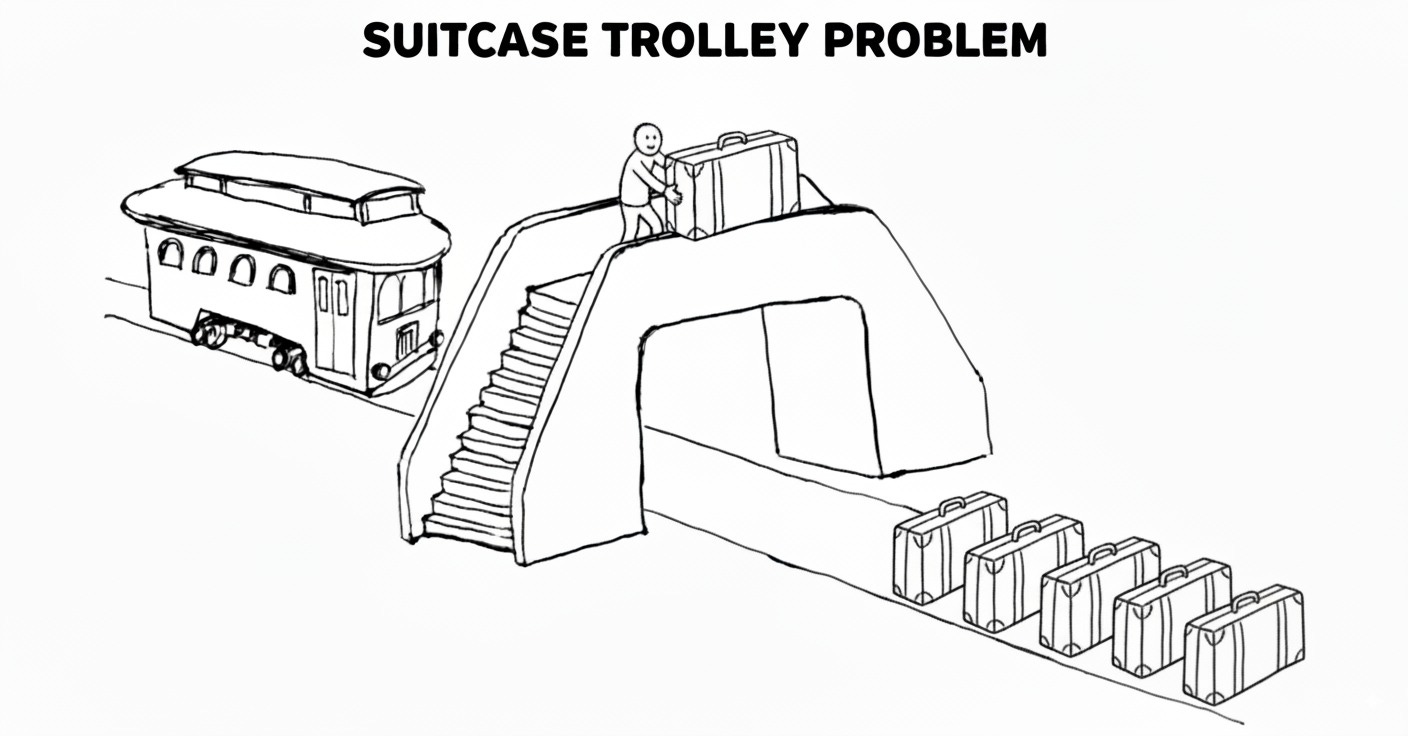

To begin with, suppose that all affected parties were behind a “veil of ignorance”, or had been stuffed into suitcases and couldn’t tell which position in the Trolley Footbridge scenario they were in. But they had their smartphones with them, and we were able to push a digital poll: would they prefer for us to leave the five suitcases on the track to die? Or to drop the one suitcase from the footbridge, killing that one while saving the five? Every single person, if prudent, will respond by asking that we drop the one. More specifically, each consents to being killed in the event that they are the one, conditional on the other five doing likewise and thus overall increasing their chances of survival from 1/6 to 5/6. In this case, I take it that we obviously ought to follow the universal consensus request of everyone affected, and kill the one (with their consent) to save the five.

What if we can’t communicate? We have two options. We could assume that rights are inviolable (in the absence of explicit consent), and so leave the five to die. Or we could do what we know full well that everyone in the situation would (on pain of irrationality) want and ask us to do, if only they could communicate. The latter option seems clearly better and more respectful of the affected individuals. So we should kill the one (even on the basis of imputed rather than explicit consent) to save the five.

Now, it’s worth pausing a moment to deal with the objection that hypothetical consent is “not worth the paper it’s not written on.” Consent can play different normative roles, not all of which can be filled with merely hypothetical consent. Some (e.g. sexual) examples involve consent playing a transformative role in changing the very nature of the action that’s performed. (What one would consent to is then a different action from what is done in the absence of one’s actual consent.) But for a more generic counterexample: suppose that you would have sold your lottery ticket for an above-market price (before anyone knew the winning numbers). Even so, this clearly does not imply that you’re committed to selling it to someone who knows both what the winning numbers are and what your numbers are, and is in a position to exercise discretion about whether or not to “enforce” the hypothetical contract—e.g. by buying the ticket only if it is a winner.

As this example shows, you would be vulnerable to exploitation if you allowed the discretionary enforcement of merely hypothetical contracts: people will offer to buy your winning lottery tickets but not your losing ones. That’s a bad deal! We may need actual contracts in order to ensure that everyone is on the same page about what is going to be enforced, to ensure that you have a chance to reap the upsides of a deal and not just the downsides. Otherwise, the “deal” is not actually in your ex ante interests: you didn’t really have a chance to win, because your gambling partner only follows through in the event that doing so serves them rather than you.

This objection suggests that we need to protect against the risk of discretionary enforcement of hypothetical deals. It would not be OK for the agent to be disposed to kill the one if and only if the one turned out to be Bob in particular. That disposition would mean that the imputed “deal” was not actually in Bob’s ex ante interests: if he were one of the five, the agent would not have killed another in order to save him (along with the four others).

So, to be clear, the principle I’m appealing to is not that you can enforce hypothetical deals on a discretionary basis, or whenever it seems convenient to the agent given who ended up in which positions. That would undermine the reasoning of ex ante mutual benefit. Rather, my principle is that one ought to enforce a rationally-mandated hypothetical precommitment when one is robustly disposed to do so no matter the particular identities of who turns out to win or lose from this.1 When the agent thus follows a policy of saving the most lives (and isn’t just opportunistically killing off an enemy), this policy best serves the ex ante interests—and hence (in the absence of countervailing reasons) the rationally-mandated preferences and hypothetical precommitments—of every agent in the situation prior to their learning what specific position they are in. That plausibly makes it the morally best policy to follow in the circumstances.

Next, we may consider how things change when participants know their positions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Thoughts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.