Inviolability and Importance

Kamm vs Kagan on Maximal Moral Status

In her 1992 ‘Non-Consequentialism, the Person as an End-in-Itself, and the Significance of Status’, Frances Kamm defends and motivates deontic constraints by appeal to the “moral status” she takes to be associated with “inviolability”:

If we are inviolable in a certain way, we are more important creatures than violable ones; such a higher status is itself a benefit to us. Indeed, we are creatures whose interests as recipients of such ordinary benefits as welfare are more worth serving. (p. 386, emphasis added)

Many people seem to share this sense—they feel that utilitarianism is somehow disrespectful in how it regards our value as persons—but I don’t get it; it rather strikes me as the sort of thing a confused undergrad or LLM might write by stringing together evocative words without pausing to check whether the idea thereby expressed actually makes any sense. (It just seems transparently silly to claim that a prohibition against saving more of some class of creatures, at the cost of a few, is a sign of how important those creatures are. Like the inverse of the old joke about the restaurant where the food was impalatable and the portions too small.)

As Shelly Kagan explained in his ‘Replies to My Critics’1, you might be more important if you were the only person who was inviolable in this way: if others’ interests had to be sacrificed to advance yours but not vice versa. Universal inviolability, by contrast, is clearly a two-edged sword: it means you can’t be hurt to help others, but it equally means that you are less apt to be helped: “There is a sense in which I am revealed to be more important if others must come to my aid, putting aside their own interests so as to serve my own.” (Kagan 1991, p. 920.)

So, if everyone is to have the same set of rights, while the right to be aided and the right against interference conflict, which right is more valuable or “reveals us to be the most important sorts of creatures”?

In a footnote, Kagan suggests that “One might… try to settle it by asking which set of features it would be rational for me to select, given that others are to have the same moral standing. Or perhaps we might turn to a contract approach, and ask what features rational bargainers would settle upon.” (p. 920, n.1)

If that’s the right diagnostic test, my argument in From Autonomy to Utility suggests that we should prioritize the right to be aided. (From behind a veil of ignorance, we’d all have decisive reason to mutually contract away all non-utilitarian rights in order to improve our prospects.)

Kamm’s Response

Kamm might deny that moral status is revealed by which right is better for you to possess. But then we must take care to avoid status-fetishism. Kamm thinks that nature itself would be “insulting” if it were a law of nature that a random person with healthy organs would conveniently drop dead (in a harvestable location) whenever a sufficient number of other persons were in need of organs to survive (p. 386). I find her aversion to this imagined natural law crazy.2 I know I would much prefer to live in the world where this law applied (if we can assume away moral hazard, at least: suppose this is a world where individual choices make no difference to one’s risk of organ failure), and I really think anyone who disagrees due to sensitivity to perceived slights from nature is failing as a rational being and needs to get over themselves. Pride so deleterious to one’s chances of survival is ridiculous deeply misguided.

Kamm acknowledges Kagan’s challenge: “We need a good justification for why—as I believe is true—our own status as a person goes down rather than up if a great deal may permissibly be done to persons to save us.” (p. 388) She continues:

Suppose the high status of persons, making it important to save them, was held to stem from some other property. Then to say that their status would go down if they were violable (in certain ways) is to claim that the properties that underlie one’s inviolability are more important than those that give rise to any other significance one has. For example, having a rational will, whose consent we must seek when interfering with what a person has independently of us, will give a person higher status than being a complex, feeling creature who cares about whether it lives or dies.

Three problems with this reasoning:

(1) The second sentence is a non-sequitur. We may all agree on what non-normative properties people have—rational wills and all that. Our having these “important” properties (and hence the status that goes along with them) does not depend on the properties additionally giving rise to rights against interference. The importance of rationality does not entail the importance of whatever dubious normative claims one regards as “stemming” from rationality. If one questions why we should valorize inviolability, the mere fact that you regard it as stemming from an important trait provides no reason at all to think that it has any additional importance in its own right. (I could think that possessing a rational will makes one immune to criticism, but my offering this proposal hardly guarantees that we are actually “less important” as a species if it turns out that we are actually allowed to criticize each other’s bad arguments.)

(2) I’m not sure what it means to say that having a rational will is “more important” than being a sentient (complex, feeling) creature. If I could only have one or the other—either be a rational zombie or a sentient non-rational animal—sentience seems more essential (in a “hierarchy of needs” sense). OTOH, I do think that being a (rational and sentient) person is more than twice as good3 as merely being sentient, so maybe it is “more important” in that sense.

(3) As my previous sentence brings out, one may just as well take having a rational will to be what underlies the especially high status of persons (compared to other sentients) as welfare beneficiaries. So we both have: (i) no argument for why having a rational will would ground inviolability, and (ii) no argument for why having a rational will couldn’t ground high status as a welfare beneficiary. It just seems like a total failure to say anything remotely convincing or rationally supportive of the conclusion that Kamm is trying to establish. Baffling stuff!

People and Animals

Earlier (p. 386), Kamm offers what we might call an ‘argument from speciesism’:

Kagan claims that the only sense in which we can show disrespect for people is by using them in an unjustified way. Hence, if it is justified to kill one to save five, we will not be showing disrespect for the one if we so use him. But there is another sense of disrespect tied to the fact that we owe people more respect than animals, even though we also should not treat animals in an unjustified way. And this other sense of disrespect is, I believe, tied to the failure to heed the greater inviolability of persons.

An interesting point of contrast: sometimes supporters of euthanasia, in reflecting on the ways that “sanctity of life” ideologues deprive people of the autonomy to choose the manner of their own deaths, say things like, “We wouldn’t treat a dog this way.” I think there’s an important insight here: misguided moralism sometimes risks leading us to treat people worse than animals (prioritizing symbolism over real interests).

Of course, there are more human-friendly ways to show greater “respect”. People may have stronger claims on our aid, and hence neglect of our interests may be harder to justify than would similar neglect of non-human animals. Many people seem to think that we have no reasons at all to aid wild animals. (Kieran Setiya says something along these lines in his paper ‘Humanism’.) Seems like an awfully callous view to me, but to those who accept it, they can certainly account for owing people “more” without cursing us with inviolability, sanctity, or other detrimental statuses that any actually-rational species wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole.

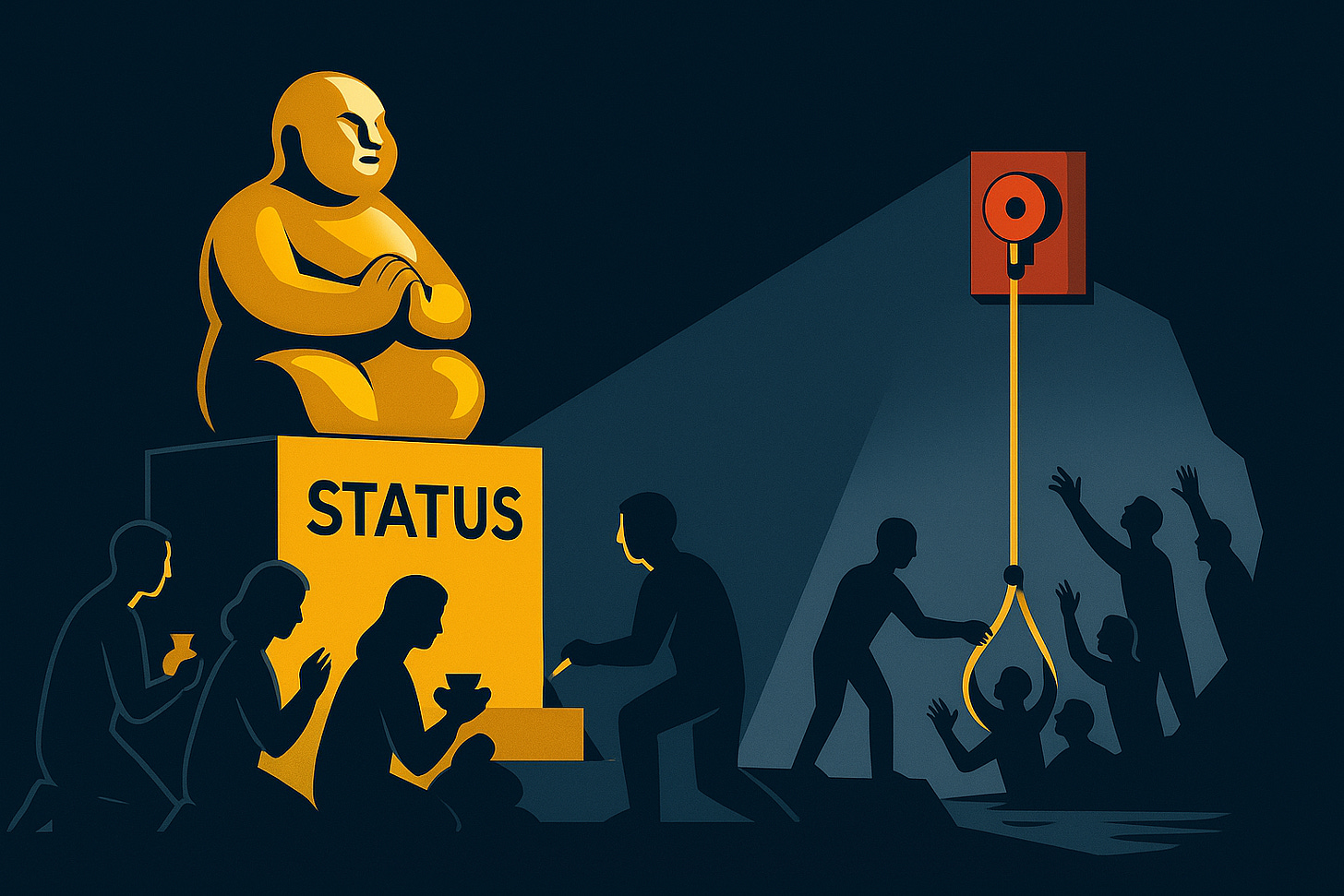

I guess what’s really going on here is that Kamm is channeling the intuition that people are sacred. Our cognitive modules for sacred valuation resist acknowledging tradeoffs or otherwise engaging in intelligent thought. (Explains a lot!) According to religious thinking, sacred objects are inviolable and also especially high status. But religious thinking is notoriously… unclear… which is why there are no comprehensible arguments for this whole line of deontological thought. You have to already be a member of the faith, or it’ll just sound like so much mumbo-jumbo.

Responding to an earlier paper of Kamm’s that makes similar points.

She claims that “In such a possible system of nature, people are treated as mere means to the welfare of others, and not also as ends-in-themselves.” (pp. 385-6.) This is silly. Insofar as we can personify nature as “treating” people like anything at all, you are (obviously!) treated as an ultimate end when your interest in survival is given such weight that others must be sacrificed in order to save your life. And everyone’s interests are given this weight.

See also my article on The Mere Means Objection, where I discuss more of Kamm’s claims about “mere means” in the context of (her prohibiting) prioritizing saving the life of a pharmacist who will go on to save several more lives. If anyone thinks a rational defense of Kamm’s view of the pharmacist case is possible, I’d love to hear it!

In terms of welfare capacity or the prospective value of one’s life.

Hope you don’t mind if a crazy person leaves a silly comment!

“Pride so deleterious to one’s chances of survival is ridiculous.”

Really? Even if you’re a utilitarian, there are obvious game theory reasons why you should want to have pride (even if this commits you to unreasonable actions in some eventualities). If it’s clear that you won’t put up with humiliation, a would-be exploiter can’t use your self-interest against you. This is, as a matter of empirical fact, the reason why people across cultures and income-levels are so difficult to exploit in an ultimatum game. If I know you’ll turn down an unfair split (even at great cost to yourself), I have an incentive to make a fairer offer.

Moreover, strategy aside, I find it hard to ridicule people who choose to die rather than disavow their most cherished values. This is not an obscure idea! Look at the treatment of martyrs in religious history. Or, to give an example from popular fiction (spoiler alert for Watchmen), think of how Rorschach chooses to be incinerated rather than step aside.

Maybe they’re making a subtle mistake, or maybe they got unlucky, having internalized a value that commits them to destructive actions in unfortunate circumstances. But “ridiculous”? I don’t see it.

Is "Never Let Me Go" your favourite romantic comedy?