Deontologists Shouldn't Vote*

Quiet Deontology Wants Out of the Public Sphere

* (Unless, of course, their vote would help to prevent an even worse outcome.)

In ‘The Curse of Deontology’, I introduced the distinction between “quiet” and “robust” deontology, and referred to my paper refuting the latter. The upshot: deontologists are stuck with the “quiet” view on which no-one can want anyone else to follow it. (Think of it as consequentialism modified by an overriding constraint against getting your own hands dirty. Crucially, you have no reason to want others to prioritize their clean hands over others’ lives.) Quiet deontologists want the consequentialist outcome, they just don’t want to dirty their hands in pursuit of it.

A striking implication of this view is that deontologists should refrain from publicly disparaging consequentialism or trying to prevent others from acting in consequentialist-approved ways. (They may be constrained against lying or positively assisting in wrongdoing, but there’s no general obligation to speak up in harmful ways. Compare Kantians on lying to inquiring murderers vs refusing to answer.) In this post, I’ll step through some examples of this principle in action.

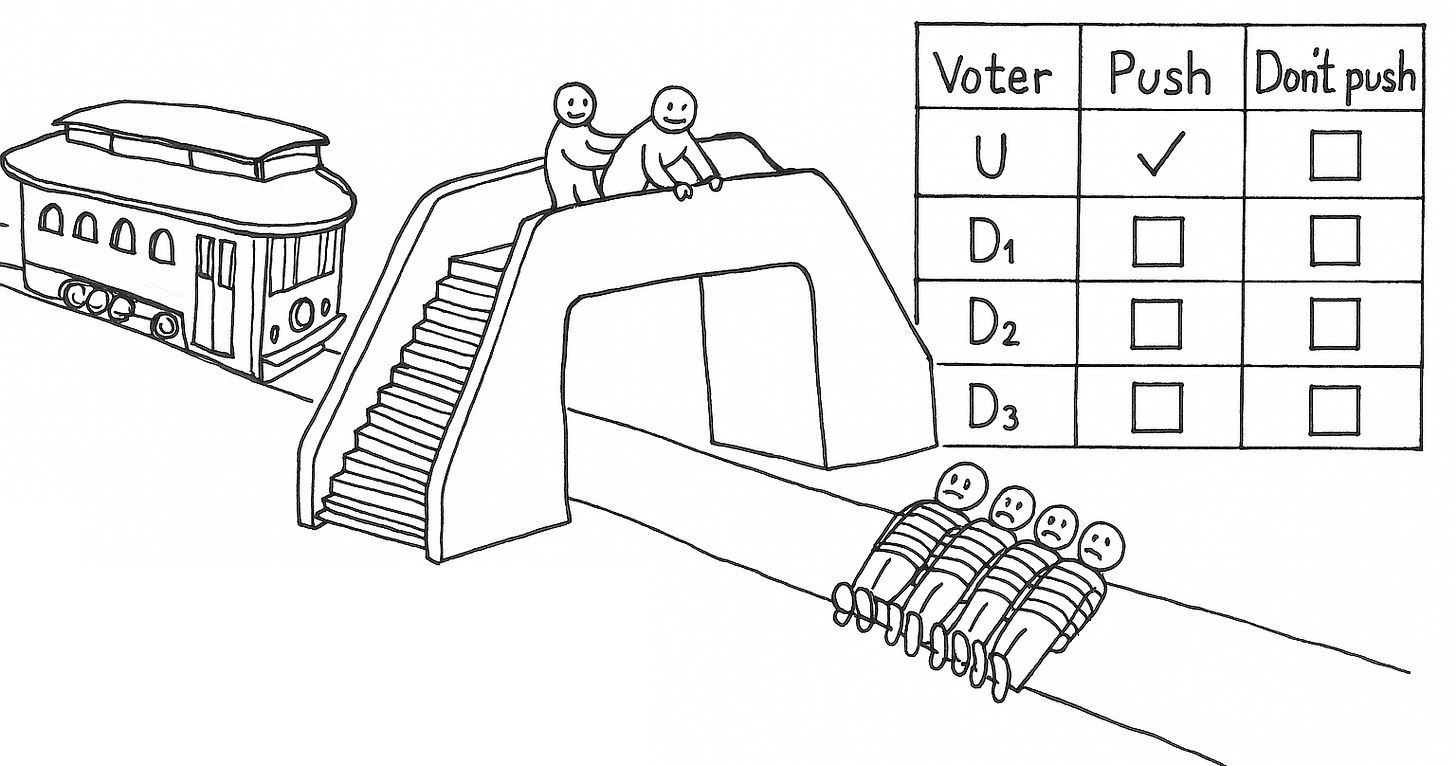

Voting on Trolleys

Consider Voting Footbridge: a trolley will kill five, unless a robot pushes a fat man in front of the trolley to stop it first. The robot is controlled by the majority vote of a group of onlookers consisting of one utilitarian and several quiet deontologists. What should the deontologists do (by their own lights)?

Abstain, presumably. Voting to push might make them complicit, and they care about their clean hands more than anything else in the world. But they have no reason to vote against the robot pushing. They want the robot to push! (That’s what makes them quiet rather than robust deontologists.) So they should abstain, and let the utilitarian’s vote carry the day and “wrongly”—but heroically—save the five for them.

After all, there’s no general obligation to vote. We may be obliged to bring about vastly better outcomes, including via voting when our doing so would have that effect. But the sheer act of voting, e.g. on trivialities, is hardly mandatory as such. Moreover, deontologists are generally fine with allowing people to refrain from doing even very good things (like donating to effective charities). So they surely can’t demand that people go out of their way to make things worse. (That would be an insane demand.) So, in particular, there’s no obligation to wrestle the utilitarian for control of the robot. Just sip your tea and leave it be.1

Bioethics and Public Policy

This point generalizes in ways that are extremely practically significant. Public policy is routinely distorted by moral idiocy. A vast number of mutually-beneficial exchanges—from life-saving kidney markets to poverty-relieving guest-worker programs—are opposed by utopian enemies of the better who sacrifice individuals for symbolism and consider themselves “moral” for doing it. Research prudes oppose monetary incentives to participate in socially valuable clinical trials. Right-wing propertarians don’t even want to see other rich people taxed for the greater good, nor artistic works made more broadly accessible without the permission of the copyright “owner”. Everywhere, we see people urging each other to be selfish.

None of this makes the slightest bit of sense if “quiet deontology” is correct, because other people doing the consequentialist thing doesn’t dirty your hands.

Again: quiet deontologists want the best outcome to happen, they just don’t want to be personally responsible for it. So, let’s say it again: sip your tea and leave it be. Stop publicly arguing that good things would be “exploitative” or “wrong”. Even if it’s true, you shouldn’t want others to believe that. You should want them to do the thing that results in a better future. (Who cares if they act wrongly? Not quiet deontologists!) So, sip your tea. Let the consequentialist ethicists own the public sphere. If you’re tapped to join the President’s Council on Bioethics? Decline it and recommend Peter Singer as someone better qualified for the role. (Deontology disqualifies you, because it makes you not want other people to do the right thing. Consequentialists, by contrast, can happily take on roles as public moral advisers without compromising their integrity.)

Isn’t this all terribly odd?

Personally, I think principled deontologists should repudiate the “quiet” view and go all-in on trying to find a way to rescue the robust view from my new paradox! But most ethicists evidently disagree. With the honorable exceptions of Jake Zuehl and Andrew Moon, I think every deontologist who has offered feedback on my paper so far (including every critical referee across several journals) ended up endorsing the quiet view. One top journal went so far as to reject the paper as “uninteresting” because they thought it was so obvious that all contemporary deontologists embraced the quiet view. They thought I was targeting a straw man by discussing the robust view at all!

If that sociological claim is correct, then contemporary deontologists should be just as horrified as I am by the role that deontology plays in the public sphere, obstructing beneficial policies for “moral” reasons that are fundamentally anti-social or contrary to the social good. Again, they may think it would be “wrong” for policy-makers to implement the consequentialist policy, or for others to vote for it. But they should hope to see it happen nonetheless. And so they should at least refrain from acting as an obstacle themselves.

Now, if my paradox of robust deontology is successful, everyone (with no personal interests at stake) must prefer to see consequentialist public policies implemented.2 If your scruples don’t allow you to participate in the implementation, you should—by your own lights—move aside so that others bring about the future that you agree is morally preferable. This may include educating the public—and professional “bioethicists”—to be more consequentialist, so they don’t put political pressure on policymakers to do awful things like prohibiting kidney markets, euthanasia, embryonic selection, or vaccine challenge trials.

I look forward to seeing how prominent deontologists grapple with this challenge: Why (when you have no personal interests at stake) would you try to get other people to act in ways that make the world worse?

Popular civic ideology pretends that citizens—and especially non-voters—are automatically “complicit” in whatever their government does. Reflection on Voting Footbridge should suffice to reveal this claim as baseless. For further discussion, see my response to Arnold in Questioning Beneficence.

Technically, this still leaves open how you assess outcomes as better or worse—you needn’t accept the utilitarian’s axiology in particular. All that’s being ruled out here is concern specifically for others violating constraints or acting wrongly. You could, for example, endorse a consequentialism of rights that sought to impartially minimize rights violations. But I’m not aware of anyone who seriously defends such a view. So I assume most would end up endorsing an axiology that’s at least sufficiently similar to utilitarianism as to agree on the sorts of policy issues mentioned in this post.

As I've mentioned before, I think there's an even simpler version of the puzzle that has the advantage of *actually being explainable in conversation*. I think when we discussed it though you mentioned thinking it had some small disadvantage (which might be right!) But the core idea is as follows.

Imagine three states of affairs:

1) Person A kills one person to stop B and C from killing one person each.

2) Person A kills one person indiscriminately. B and C do not kill.

3) B and C kill indiscriminately.

Clearly 1>2>3. So then the third party prefers the state of affairs with one killing to stop two killings to the one where 2 killings happen. But if one prefers a state of affairs where some agent acts in some way to one in which they don't, then it seems they prefer the action.

I think this argument is basically totally decisive. It shows that deontologists have to be quiet in the sense that you describe. But quiet deontology is hugely problematic. First of all, it's just wildly counterintuitive that God should be sitting in heaven hoping that people do the wrong thing.

Second, as you note, it seems that hoping is tied up with all sorts of other commitments--e.g. what you should vote for. So the deontologist shouldn't vote to stop the killing and organ harvesting or pushing people off bridges.

But things get even weirder! Presumably if you want X to happen, you shouldn't stop X. But deontologists would generally be pretty uncomfortable thinking that you shouldn't stop killings to save multiple lives. The person going around killing and harvesting organs should be stopped if deontology is true.

Similarly, should you try to persuade them out of it? If you should want a person to X, then you shouldn't try to stop them out of Xing. So then if your utilitarian friend asks if they should kill to save lives, the deontologist should say: "yes." They should even lie--for lying is worth saving multiple lives.

At this point, deontology begins to look weirdly egoistic. You want everyone else to breach the moral norms--you just don't want to get *your* hands dirty! You even should trick them into following it.

Should you then hope that you do the wrong thing in the future? Either answer is weird. If so, that is pretty insane. If not, then if you watch some person doing some wrong action in a screen and have dimension, whether you should hope they do the wrong thing will depend on whether they are you. Nuts!

Generally we think a big advantage of murder laws is that they deter crime. Deontologists must think that at least regarding murders that prevent multiple other lives saved, the fact that laws against those deter committing them is a bug not a feature. And this is so even though killings to save lives are morally wrong.

(Unrelated: this argument was one of the things that got me seriously thinking about ethics. I remember puzzling over it for a long time--and thinking it illustrated both how to do good ethics and what was wrong with deontology. It inspired a lot of other arguments against deontology for quite a while. I can't tell if this or you 2-D semantic argument against moral naturalism is my favorite argument from you).

I really enjoy the paradox paper. I do find it quite counterintuitive to think about what we have reason to prefer and what we have reason to do coming apart in this radical way. I take it the deontologist has to bite this bullet or show we shouldn't always prefer better states of affairs (or perhaps deny that we have reasons for any preferences?). Showing we shouldn't always prefer the best seems preferable (heh) to me, since I'm already convinced I have reason to prefer a case in which, say, my child lives and two strangers die. But there is something weird about saying, when nothing that we (appropriately) care about from the agent-relative perspective is at stake, we shouldn't always prefer the impersonally better outcome/state of affairs. I take this is something the failed rescue vs successful rescue is meant to bring out. I'm not entirely sure what to say. I look forward to seeing the responses to the paper.

I do think you're being unfair to the quiet deontologist when you make it sound that what they 'want' is to avoid acting wrongly (i.e. "quiet deontologists want the best outcome to happen, they just don’t want to be personally responsible for it"). Quite deontology, I take it, is the position that what you have reason to want comes apart from what you have reason to do. It seems then that quiet deontologists have reason to prefer that they act wrongly. They just can't do it! Now, this strikes me as very weird. But do we sometimes have such preferences? One could imagine a judge who is duty-bound to condemn his son to death and does so, but wholeheartedly prefers the world in which he fails to do his duty. How weird is that? I don't know.

It is worth noting, though, that we might have very strong reason for preferring that the public sphere not be dominated by consequentialist thinking, even if we are quiet deontologists--it might be that unchecked consequentialism could lead to, or simply constitute, a worse state of affairs. So in that regard, the quiet deontologist may not be condemned to acting against what she should prefer.